An article on Jose Maria Sobral is out. It was published in the Antarctic Magazine, Vol 38 Nos 1&2, 2020. If you are an Antarctic Society member, than you have seen it already. However, for non-members, I show the article here, please see below. This is the latest version I sent in for publishing, so there might be slightly differences in the text and the photos and map are not included.

José María Sobral – an Argentinian on a Swedish Expedition

Introduction:

José María Sobral (1880–1961) is considered as the “father of the Argentine Antarctic”. He was the first Argentinean who overwintered on the Antarctic Peninsula (figure 1) and who was awarded a doctoral degree in Geology. As a young navy officer, he was chosen to take part in the Swedish Antarctic Expedition (1901–1903) led by Otto Nordenskjöld (1869–1928). This is the story of a man who was a talented officer, scientist, and author, but who hardly received the recognition he deserved during his lifetime. For his entire professional life he felt isolated.

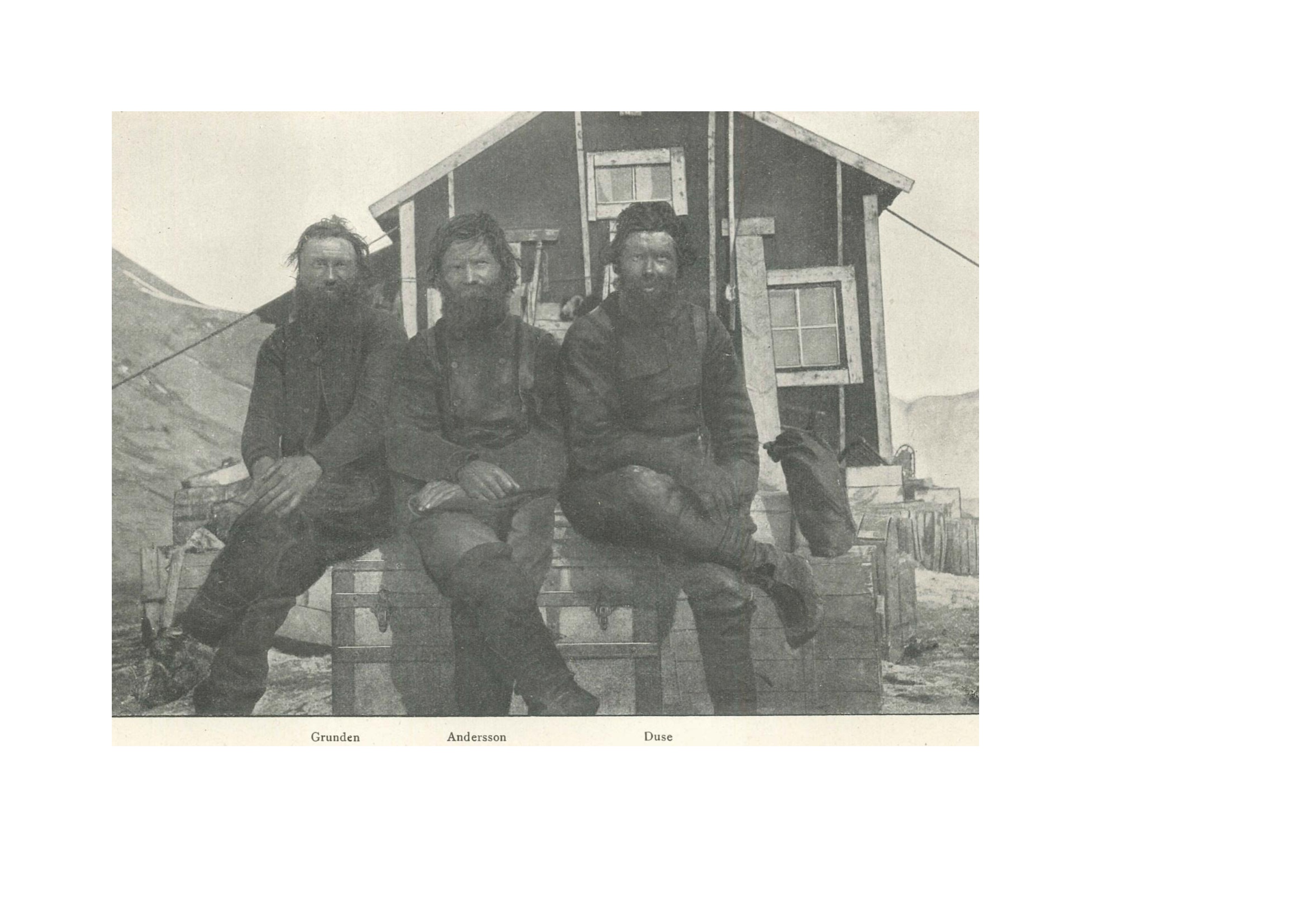

Sobral was a twenty-one year old navy officer (figure 2) when he was chosen to join the Swedish Antarctic expedition. This arrangement was driven by the need for Argentinean support and supplies, which is why Nordenskjöld in exchange accepted the young navy man in his ranks. The Swedish scientists struggled to fully accept Sobral because of his temperament and choice of clothing. It was too “Southern” for their taste. Captured in strong class thinking, the serious scientists from the North had avoided the light hearted “Southerner”. Sobral was quite isolated and the Swedish scientists seem to have failed in integrating him. Nordenskjöld was his only attachment figure for a long time and he even taught him Swedish. From that moment on, he became a bit more accepted but was still not seen as equal. The impression of how much manliness and maleness Sobral as a person made had in impact on the group dynamics and is very well discussed in Lisbeth Lewander’s work on gender differences within the Swedish Antarctic expedition (Lewander, 2001). For some, Sobral was not manly enough compared to the hard working Norwegian grew and the “white” Swedish scientists.

Sobral was part of the overwintering party on Snow Hill Island (figure 3) and it turned out that he had all the ingredients for a great scientist. He also worked hard on the sledge journeys and as a meteorologist and he was a fast learner. When the expedition was rescued after two years (see Antarctic Magazine, issue 245, vol 36, no 3, 2018) Sobral went back to his former navy position. He took courses at Buenos Aires University (School of Exact, Physical, and Natural Sciences) in geology, petrology, and hydrology. As the Navy did not support his decision to become a scientist he had to resign from his position. Sobral went to Uppsala, Sweden, where he was awarded a doctoral degree for his studies in geology and hydrology. In 1906, he married Elna Wilhelmina Klingström in Sweden and with her he had nine children. In 1914, he returned with his family to his homeland Argentina but it turned out that he did not fit in here once again (Tahan, 2017, pp xi-xiii). He travelled through Argentina and studied its geology and held different positions in various state departments, gave public lectures, and became a writer. Publishing books on the Army and Navy, the Argentine-Chilean relations, the peaceful occupation of the Antarctic, geological studies, as well as books on his Antarctic adventures, brought him some publicity. Although Sobral was awarded a “Naval Cross for Distinguished Services” he has not received full acknowledgement for his work as a scientist. He died in the house he was born on 14 April 1961 on his 81st birthday, coincidentally in the same year the Antarctic Treaty entered into force.

Since then, Sobral is celebrated for his “Argentinean firsts”: overwinterer in the Antarctic and recipient of a PhD in Geology. As a national hero he is exploited to underpin national interests in the Antarctic. Nowadays, a navy boat and a station in the Antarctic is named after him. During his life-time, however, his achievements have been overlooked. Since his Antarctic diaries are published in English he is slowly gaining visibly in the wider Antarctic Community.

References:

Lewander, Lisbeth; (2001) Gender Aspects in the Narratives of Otto Nordenskjöld’s Antarctic Expedition, in: Antarctic Challenges. Historical and current perspectives on Otto Nordenskjöld’s Antarctic expedition 1901–1903. (edit: Elzinga, Aant; et all) Göteborg: Royal Society of Arts and Science, pp 98-120

Nordenskjöld, Otto (edit.); 1910. Wissenschaftliche Ergebnisse der Schwedischen Südpolarexpedition 1901–1903, vol 2: Meteorologie. Stockholm: Lithographsiches Institut des Generalstabs

Nordenskjöld, Otto (edit); 1904. Antarctic. Zwei Jahre in Schnee und Eis am Südpol. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer, vol.1

Tahan, Maria; (2017) The life of José María Sobral. Scientist, Diarist, and pioneer in Antarctica. Cham: Springer, ProQuest ebook: https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783319672670